This musician, by all outward appearances devoted to jazz (as opposed to classical or pop) is moved in his soul more often than not by music that is not jazz. How can it be that a jazz piano student enjoys listening to and playing music of the European masters more so than jazz?

What am I to make of this? Have I come 4400 miles across the sea for a chasing after the wind?

I refuse to accept that.

Instead I cling to this: jazz is less of a type of musical product and more a musical process. This is a robust solution to my problem: firstly, it frees me from the anxiety caused by leaving everything I know and love behind to pursue one thing, only to then find out I don’t really like that one thing so much; secondly, it lays a firm and versatile foundation for musical growth.

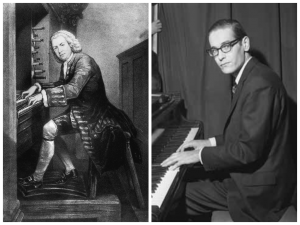

When interviewed by his older brother, Harry, pianist Bill Evans explained that jazz is a revival of what went on in Western music centuries ago: in the 17th century there was a great deal of improvisation in music. Since there was no way to record and then reproduce music as we now have thanks to electricity, music had to be committed to paper, a medium rather remote from what music actually involves. Over time, improvisation and learning music aurally gave more and more ground to the composing and interpreting of written music. The terminus of this process is what we see today: music is created and interpreted via visual media; improvisation is nowhere to be found in the typical recital or concert, and is so removed from everyday musical education that at Gustavus it is taught as an elective rather than as an aspect of primary lesson instruction. There is a practical denial of improvisation’s central role in music.

Jazz, then, is an affirmation of improvisation’s value. Granted, because of historical and cultural circumstances, jazz tends to be thought of as a category of musical product, a stylistic idiom: the melody and harmony of the late Romantic era influenced to varying degrees by African rhythms and traditionally presented in popular song form. But these things are not what sets jazz apart. What distinguishes jazz from classical music is the process: jazz musicians do not spend hours in the practice room trying to interpret what a composer has penned. Instead, they spend hours in the practice room developing the technique and creative abilities necessary to spontaneously compose music.

So it is perfectly fine for me, having left everything behind to study jazz, to still prefer Debussy to Chick Corea: the fact that something happened to be created with the process I love does not necessarily mean that I will enjoy it more than music composed in a different manner.

This understanding of jazz serves as a solid foundation for further musical growth because the process is not exclusively related to jazz. Improvisation does not belong exclusively to jazz music; this only seems true because classical music has more or less given up on improvisation in order to plumb the depths of interpretation. In sowing into the study of the jazz process, I will reap a great benefit that can be applied to any kind of music I wish to create: the creative processes I am developing are more versatile and easily transferable than their final products.

Thus we have come full circle: when troubled because of an occasional lack of care for the jazz music around me, I reassure myself that I belong here for the sake of the process, not the product.

What a relief. As previously promised, my next post will address the conservatory itself.